Openness and praxis (at #SRHE)

This blog post is a summary of my presentation at SRHE (Society for Research into Higher Education) in London on November 18, 2016. The event was organised by the SRHE Digital University Network, convened by Lesley Gourlay, Ibrar Bhatt, and Kelly Coate. The theme was Critical Perspectives on ‘Openness’ in Higher Education. Three of us shared our research: Muireann O’Keeffe, Rob Farrow, and myself. Sincere thanks to SRHE and DUN organisers for the kind invitation, to Muireann and Rob for their thought-provoking presentations, and to all who attended for sharing their ideas. Following is a short summary of my presentation.

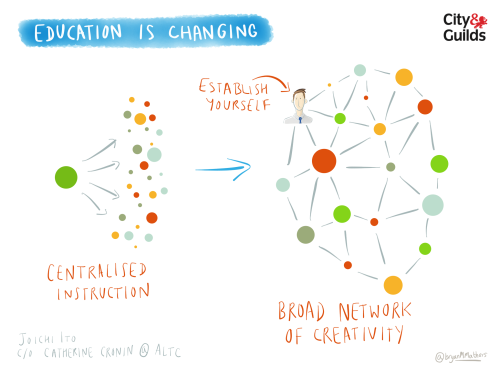

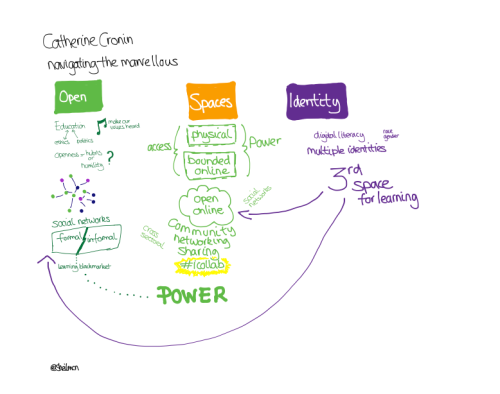

I begin with a reflexive note. I first shared the above quote by Michael Apple during ALT-C in 2014, a conference held in the weeks immediately following the start of both the Black Lives Matter movement and Gamergate. We continue to live in uncertain – and for many, perilous – times. As educators, we face fundamental questions about education, democracy, and inequality. How are we developing digital and media literacies, data literacy, civic literacy, digital citizenship? What is the purpose of our work as researchers and educators? What is the role of higher education, and of public higher education? I am an open researcher as well as an open education researcher. I believe openness has the potential to increase access to education, to help to democratise education, and also to prepare learners in all contexts for engaged citizenship in an increasingly open, networked and participatory culture. But openness is not without risk. Openness can as easily exacerbate inequality as help to reduce it. We need more than good intentions. We must theorise openness and we require critical approaches to openness in order to realise the benefits in any meaningful way. This has been the impetus for my work and I begin my presentation with that reflexive framing.

…

The title of my presentation is ‘Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices (OEP) for teaching in higher education’. I use the word praxis as Freire (1970) defined it: “reflection and action directed at structures to be transformed”. I’ll briefly describe the preliminary findings from Phase 1 of my PhD research study – a qualitative, empirical study exploring meaning making and decision-making by university educators regarding whether, why, and how they use OEP for teaching. It is a study not just of open educators, but of a broad cross-section of academic staff at one university. The purpose is to understand how university educators conceive of, make sense of, and make use of OEP in their teaching, and to try to learn more about, and from, the practices and values of educators from across a broad continuum of ‘closed’ to open practices. (A subsequent phase of the study will include the perspectives of students re: openness.)

Defining OEP

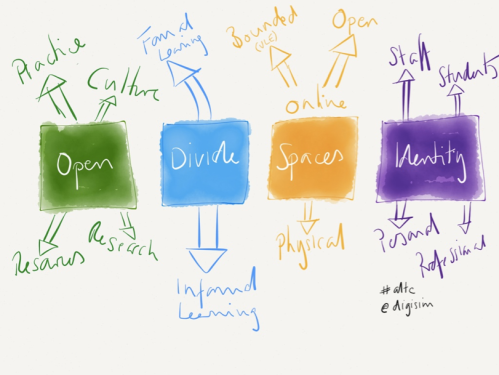

Overall, open education practitioners and researchers describe OEP as moving beyond a content-centred approach to openness, shifting the focus from resources to practices, with learners and teachers sharing the processes of knowledge creation. In their summary of the UKOER project, for example, Beetham, et al. (2012) explicitly define the project’s interpretation of OEP as practices which included the creation, use and reuse of OER as well as open learning, open/public pedagogies, open access publishing, and the use of open technologies. Ehlers (2011) defines OEP as “practices which support the (re)use and production of OER through institutional policies, promote innovative pedagogical models, and respect and empower learners as co-producers on their lifelong learning paths.”

Education researchers and practitioners have described and theorised some or all of the practices defined here as OEP using a variety of definitions and theoretical frameworks. These include open pedagogy (DeRosa & Robison, 2015; Hegarty, 2015; Rosen & Smale, 2015; Weller, 2014), critical digital pedagogy (Stommel, 2014), open scholarship (Veletsianos & Kimmons, 2012a; Weller, 2011), and networked participatory scholarship (Veletsianos & Kimmons, 2012b). All are emergent scholarly practices that espouse a combination of open resources, open teaching, knowledge creation and sharing, and networked participation. I have drawn from research in all of these areas to inform my work.

I use the following definition of OEP in my study: collaborative practices that include the creation, use and reuse of OER, as well as pedagogical practices employing participatory technologies and social networks for interaction, peer-learning, knowledge creation, and empowerment of learners.

The study

The goal of this first phase of the research study is to understand why, how, and to what extent educators use, or do not use, OEP for teaching. The study was conducted at one university in Ireland: a medium-sized, research-focused, campus-based university offering both undergraduate and postgraduate degrees. Openness was not one of the mission statements or core values of the university at the time of this study. I conducted semi-structured interviews with 19 educators across multiple disciplines. Constructivist grounded theory was used for sampling, interviewing and analysis.

Summary of findings

- A minority of participants used open educational practices for teaching (8 of 19).

- All participants who used OEP for teaching described being open with students, i.e. being visible online and sharing resources in open online spaces beyond email and the VLE. Each has an open digital identity and shared at least one of these profiles with students as a way of interacting and/or sharing information.

- A small subset of participants who used OEP for teaching chose not only to be open with their students but explicitly to teach openly, i.e. to create learning and/or assessment activities in open online spaces beyond the VLE. Teaching openly took different forms: inviting students to make connections, interact, and/or share information on social media (e.g. Twitter), creating courses in open online spaces (e.g. WordPress blogs), and/or encouraging students to share their work openly.

- Participants across the spectrum of ‘closed’ to open practices cited both pedagogical and practical concerns regarding the use of OEP for teaching. These included lack of certainty about the pedagogical value of OEP, reluctance to add to their already overwhelming academic workloads, concerns about excessive noise in already busy social media streams, concerns about students’ possible over-use of social media, and concerns about context collapse, both for themselves and for their students.

- While many participants who were open educators acknowledged potential risks to using OEP for teaching, they considered the benefits to outweigh the risks. According to participants who used OEP for teaching, benefits for students included feeling more connected to one another and to their lecturer, making connections between course theory/content and what’s happening in the field right now, sharing their work openly with authentic audiences, and becoming part of their future professional communities.

- Few participants mentioned OER or open licensing – unsurprising, perhaps, in an institution without an open education or OER policy. This suggests, however, that the relationship between OER and OEP might be more complex than sometimes conceived. In addition to OER leading to OEP, the reverse also may be true: use of OEP, specifically networked participation and open pedagogy, can lead to OER awareness and use.

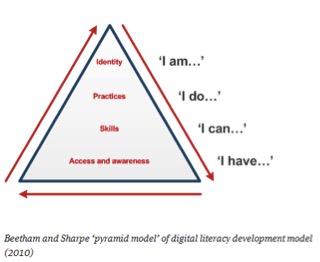

- By building a model of the concept ‘Using OEP for teaching’, it emerged that four dimensions were shared by open educators: balancing privacy and openness, developing digital literacies, valuing social learning, and challenging traditional teaching role expectations. These dimensions were shared by many participants – however all four were evident in each of the participants who used OEP for teaching. (I’ll explore these dimensions in more detail in a subsequent blog post.)

Thoughts for discussion

Openness is situated and relational. This study found educators’ use of open educational practices to be complex, personal, contextual, and continuously negotiated. Recognition of these complexities and the risks of openness and OEP, as well as potential benefits (for individuals, not just institutions) should inform higher education policy and practice. A growing body of research advocating greater theorisation and critical analysis of openness and open education is useful here (e.g. Bell, 2016; Czerniewicz, 2015; Edwards, 2015; Gourlay, 2015; Knox, 2013; Oliver, 2015; singh, 2015; Watters, 2014). In addition, attention must be paid to the actual experiences and concerns of staff and students; qualitative empirical research is essential (e.g. Veletsianos, 2015). The findings of this study suggest the need for institutions to work broadly and collaboratively to design appropriate forms of support for academic staff in three key areas: developing digital literacies and digital capabilities; supporting individuals in negotiating privacy and openness; and reflecting on the role of higher education and our roles as educators and researchers in an increasingly open and networked culture.

The research study described here is limited in scope; it explores the experiences of a relatively small number of academic staff at one university. However, it is hoped that the results provide a small contribution towards understanding how and why academic staff use open educational practices, as well as offering opportunities for further research and collaboration. This study comprises Phase 1 of my PhD research study on OEP in higher education. Two further phases building on this work are currently in progress. Phase 2 is a survey of all academic staff at the same university. And Phase 3 follows two open educators from Phase 1, as well as their students, in exploring how educators and students interact and negotiate their digital identities in open online spaces.

Many thanks. I look forward to continuing the conversation with you all.

References & links

thanks @muireannOK & @philosopher1978 🙂