#dlRN15: Hope, Hands, and Stories

And so, the Digital Learning Research Network conference. I have been mulling over all-that-was-dlRN since leaving Palo Alto a week ago. I extended my stay in California for a few days to visit family before making the long journey back to Galway. It was a wonderful and memorable week. In looking at the photos I took over the course of the week — at Stanford University and in Palo Alto, Petaluma, and San Francisco — it seems the first and last photos tell the story of the week. So I’ll start there.

‘Hope’: Stanford University Memorial Church & 575 Castro, SF

‘Hope’: Stanford University Memorial Church & 575 Castro, SF

I. Hope

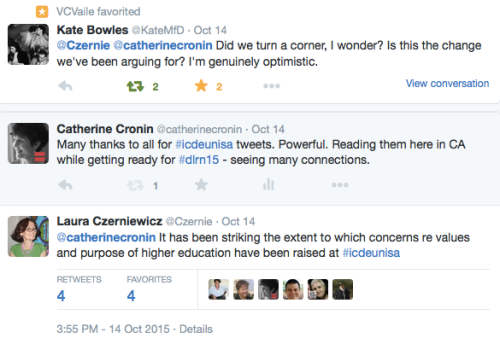

dlRN15 was short and intense (2 days + an optional pre-conference workshop). It was not a conference about tech or ‘how to’ solutions. It was a conference united around clear values, namely a social justice vision of higher education and a belief in research as a tool for advocacy or, as Kristen Eshleman wrote, “a lever for positive change”. Many of us at dlRN had spent the days preceding the conference following tweets and updates from the ICDE Conference, held in South Africa during that same week, where many of the same themes were being discussed.

After the #icdeunisa conference, Paul Prinsloo wrote beautifully about the need to reclaim the potential of education as liberation through pedagogies of hope:

Designing hope means stop speaking in the passive voice as if there were no perpetrators, no guilt, no abuse in the name of science and technology. In designing hope we need to resist these discourses and return the gaze on venture capital, on the privatisation of education, the neoliberal dogma. We need to reclaim the discourses, the commons, ourselves. We should critically look at the words we use in our strategies and planning documents and our obsession to measure, to be top, to be the best, to rise in the rankings. Somehow we must discover the beauty and simplicity of hope, and designing hope. Hope that a better life of all may, may just be possible.

The central question propelling much of the dlRN conference also — whether discussing non-traditional students, adjunct faculty, open education, MOOCs, FedWiki, learning spaces, educational philosophy, curriculum or pedagogy — was this: how can we work together to make (higher) education more equitable for all?

II. Hands

It was a privilege to engage with so many smart and kind people for 2+ days to consider this question and to try to break it down. It wasn’t all unicorns and rainbows, of course. Conversations diverged. I was frustrated, at times, at language and concerns that seemed to focus specifically on US higher education, many of which are different to issues and concerns in Ireland, Europe, and other parts of the world. But we speak from who we are and what we know. The conference chairs, Bonnie Stewart, Kate Bowles, Kristen Eshleman, Dave Cormier and George Siemens, individually and collectively created a space for dialogue that was open in the best sense — open-minded and open-spirited. We engaged with one another. I questioned assumptions — my own and others’. Sometimes we disagreed. At times we apologised. We talked, we listened. Overall, it was a space of compassion.

it seems almost

as though this is what a human life is,

to be passed from hand to hand,

to be borne up, improbably, over an ocean.

– Moya Cannon (2011) ‘Hands’

It was a privilege to share the space with so many wonderful people, not just in-person but virtually. The conference benefited immensely from virtual participation by so many. In addition to conversation channels on Twitter and Slack, the Virtually Connecting team enabled and facilitated multiple conversations. I was part of just one of these, but the full set is available on the Virtually Connecting YouTube channel. I also attended one of several conference sessions co-presented remotely by Maha Bali — this one along with the on-site Rebecca Hogue, Matt Crosslin, Whitney Kilgore and Rolin Moe. This worked beautifully for on-site participants (although I think Maha had some trouble hearing the audio on her end). We are learning. I left the conference with a deeper appreciation of the benefits and challenges of virtual participation. As someone living on the west coast of Ireland, I often rely on virtual participation in my teaching, learning, and research. After dlRN, I’m re-energised to push the boundaries even further. Thanks @VConnecting.

The most powerful part of the conference for me was the final wrap-up. I can’t recall a conference wrap-up which began with the questions asked by George Siemens: “What did we get wrong? What foundational assumptions about the conference were incorrect? and Did we surface research that will help us build towards our vision?” What a helpful starting point for post-conference activities. George Veletsianos spoke particularly powerfully in the wrap-up session, noting the need to create better futures for all students, as well as all who work in higher education. We will do this by cultivating compassion, avoiding reductionist approaches, and avoiding the creation of alternate power structures. A worthy challenge.

As I listened to the final wrap up, I sat back in my chair trying to make sense of all the emotions I felt, in awe of the capacity and willingness of the people in the room to be vulnerable, to demonstrate compassion and empathy, and their sheer resolve to make sense of the changing higher education landscape and ensure all voices are heard. I was, and will continue to be, deeply moved by it.

III. Stories

To borrow a phrase from the wonderful Kate Bowles, we brought our storied selves to dlRN. We worked hard to question and to understand one another’s stories, in order to build not just a smart but a compassionate network of researchers and practitioners to address our challenges.

My story? I travelled from Ireland to California with my wonderful daughter Sarah, a recent graduate with her own perspective on higher education. She joined me for the first day of the conference (before embarking on her own explorations) and for gatherings after the conference each day. I wasn’t the only one attending the conference en famille — we loved meeting Kate Bowles’s daughter and Bonnie Stewart’s and Dave Cormier’s children. In addition to enjoying the conference, my daughter and I met friends and family. We saw my 13-year-old niece play a home soccer game. We went on our own magical tour of San Francisco. We made memories. For one week we interwove our experiences and our dreams about work, education, family, friends, history, social justice, and the future.

My take-away from the conference is coloured by all of these experiences of the past week as well as by my position, my history, my values. And it’s simply this. There is, and will be, a plurality of voices, even when we passionately agree on the overall goal of working towards higher education which is more equal for all. We can learn much from other movements for social change — civil rights, women’s rights, gay rights, workers’ rights. At times we will feel strongly about taking different approaches to reach our goal. Some of us will want to work for incremental change, some for policy change, some for legal change, some for setting research agendas. There will be times that none of these feels like it is enough and some of us will wield placards. But as much as possible, let us value our diverse positions as we speak alongside and on behalf of students (and potential students), colleagues (particularly those with fewer rights), and all who have been left behind, knocked down, or damaged by increasingly iniquitous systems of higher education.

We will re-write this story, we will take it and reshape. There is no one counter-narrative. We want one because the Master Narrative is so strong. But it’s going to take all the stories, all the points of data. In each retelling, each instance of both telling and listening, the story changes, the story evolves, and I believe we get closer to the place we want ourselves to be.

Thanks to all those with whom I shared dlRN and all who have written their stories of dlRN. Each of you has touched me and taught me in some way. I’m sure this is not a complete list of the many dlRN blog posts, but I’ll add others as I find them. Thank you all.

- Mike Caulfield’s amazing keynote – The garden and the stream: A technopastoral

- Kristin Eshleman – #dlRN15 – Why should you trust us?

- Kate Bowles – Listening

- Lee Skallerup Bessette – #dlRN15 – A Story

- Autumm Caines – Dancing with #dlRN15

- Adam Croom – A dlRN detox and Indie music and edtech

- Tim Klapdor – #dlRN: The Cynefin of conferences

- Joshua Kim – Trying to make sense of dlRN 2015

- Laura Gogia – #dlRN15 – Early reflections from a (nontraditional) student

- Maha Bali – The #dlRN15 discourse #resonated #notresonated

- Patrice Torcivia – Making sense of #dlRN15 and Mothers (and fathers), and daughters

- Matt Crosslin – Humanize them all, and let them sort themselves out: #dlRN15 reflections

- Laura Pasquini – Digesting #dlRN15 – Making sense of higher ed

- Alyson Indrunas – Chihuahuas among the New Foundlands: The need For Communities of Practice 2.0 #dLRN15

- Jeffrey Keefer – Final musings of #dLRN15

- Michelle Pacansky-Brock – Making sense of higher ed: #DLRN15 reflections

I know that you cannot live on hope alone, but without it, life is not worth living.

– Harvey Milk

Postscript: I presented my own ongoing research at the conference in a presentation entitled: Unpicking binaries: Exploring how educators conceptualize and make decisions about openness. I’ll share more information about this in my next blog post.